Finding Nice MD5s Using Rust

A journey to try out Rust's SIMD and inline assembly

At the start of the week, a friend of mine sent me a link. "What an interesting yet pointless question!", both of us agreed. Later that day, another link was also sent to me. Apparently there was someone who did care a little bit. Out of curiosity, I opened the find_md5.py file, and it hit me: "How can I optimize this task?" The task did shout SIMD to me, and I knew rust has core::arch which provides many SIMD intrinsics. Hence my journey to try out Rust's SIMD and inline assembly began.

Introduction

By looking at zvibazak/Nice-MD5s, I got a closer picture of the task on hand. More formally we want to deal with 3 tasks:

- Randomly generate a string with 32 characters, each from

[0-9a-z]. There are some caveats on the so-called "Gold MD5", also known as the fixed point, but we will ignore that for now. - Compute the MD5 hash of the generate string.

- Compute different metrics of the hash to determine how nice it is:

- The length of the longest consecutive digits as prefix

- The length of the longest consecutive letters as prefix

- The length of the longest consecutive homogeneous character as prefix

- The length of the longest prefix matching $\pi$

- The length of the longest prefix matching $e$

Following the chronological order of me writing the code, I will first talk about how to accomplish task 3, which I call "computing niceties". For the sake of brevity, I will assume we only care about the longest consecutive digits, and only gloss over other "niceties". I will then talk about generating strings, and finally the MD5 hash computation.

The complete codebase could be found at johnmave126/nice-md5s. And for SIMD and inline assembly, we only consider x86 and x86_64 architecture.

Computing "Niceties"

We are looking for a function like follows:

fn count_leading_digits(x: [u8; 16]) -> u8;

The input is a 16-byte array (MD5 produces 128 bits, aka 16 bytes), and the output is a number counting the number of digits from the beginning. To make sense of "a digit", we break a byte into 2 nibbles, and we call a nibble n "digit" if 0x0 <= n < 0xa, and "letter" otherwise. Within each byte, we consider the most significant nibble comes before the least significant nibble.

Baseline

It is quite tempting to have a baseline algorithm as follows:

fn count_leading_digits(x: [u8; 16]) -> u8 {

x.into_iter()

.map(|b| [b >> 4, b & 0x0F])

.flatten()

.take_while(|&n| n < 0xA)

.count() as u8

}

where we construct an iterator over the nibbles from the byte array and count. It turns out that, especially in the case where we want to compute multiple metrics, it is more performant to convert the byte array to a nibble array first.

struct Nibbles([u8; 32]);

impl From<[u8; 16]> for Nibbles {

fn from(x: [u8; 16]) -> Self {

let nibbles = x.map(|b| [b >> 4, b & 0x0F]);

// SAFETY: size_of::<[[u8; 2]; 16]>() == size_of::<[u8; 32]>()

Self(unsafe { transmute(nibbles) })

}

}

fn count_leading_digits(x: [u8; 16]) -> u8 {

// Here we convert `x` to `Nibbles`, while in practice we would convert

// beforehand and reuse `Nibbles` to compute multiple metrics

Nibbles::from(x).0.iter().take_while(|&n| n < 0xA).count() as u8

}

SIMD

The first step is to load [u8; 16] into an SIMD register. We also want it to be in nibbles form for easier later processing. Conveniently [u8; 32] fits perfectly into a 256-bit SIMD vector, aka an __m256i.

I came up with two approaches to achieve this:

- Load

[u8; 16]into an__m128i, convert each byte to au16with zero extending to get an__m256i, and finally using bit shifting to adjust positions of the nibbles.unsafe fn load(x: [u8; 16]) -> __m256i { let x = _mm_loadu_si128(x.as_ptr().cast()); // Each byte now occupies 2 bytes let x = _mm256_cvtepu8_epi16(x); // Shift left to place lo-nibble in hi-byte and clear excess nibbles let lo_nibble = _mm256_and_si256(_mm256_slli_epi16(x, 8), _mm256_set1_epi8(0x0Fu8 as i8)); // Shift right to place hi-nibble in lo-byte let hi_nibble = _mm256_srli_epi16(x, 4); _mm256_or_si256(hi_nibble, lo_nibble) } - Load

[u8; 16]into an__m128i, use bit shifting to move hi-nibbles, interleave the bytes and then assemble the__m256i.unsafe fn load(x: [u8; 16]) -> __m256i { let x = _mm_loadu_si128(x.as_ptr().cast()); // Shift hi nibbles of each byte into lo nibbles // Hi-nibbles of each byte will contain some garbage now // Note: there is no `_mm_srli_epi8` let hi_nibble = _mm_srli_si128(x, 4); // Interleave // Hi-nibbles of each byte will contain some garbage let lo_128 = _mm_unpacklo_epi8(hi_nibble, x); let hi_128 = _mm_unpackhi_epi8(hi_nibble, x); // Assemble `__m256i` let x = _mm256_set_m128i(hi_128, lo_128); // Apply mask to clear hi-nibble of each byte _mm256_and_si256(x, _mm256_set1_epi8(0x0Fu8 as i8)) }

Quick benchmark showed that the two approaches had very similar performance, so I went with the first one.

Next, we want to determine whether each nibble is a digit or a letter. This is quite straightforward.

let x = load(x);

let mask = _mm256_cmpgt_epi8(_mm256_set1_epi8(0x0Au8 as i8), x);

For each byte in mask, the byte is 0xFF if the corresponding byte in x is smaller than 0x0A, and 0x00 otherwise. In other words, if the nibble is a digit, the byte becomes 0xFF. Otherwise, the nibble is a letter, and the byte becomes 0x00.

For other metrics, this kind of mask is also easy to compute.

- For longest prefix matching $\pi$/$e$, we can use

_mm256_cmpeq_epi8:let x = load(x); const PI: [u8; 32] = [3, 1, 4, 1, 5, 9, /* the rest omitted */]; let mask = _mm256_cmpeq_epi8(x, _mm256_loadu_si256(PI.as_ptr().cast())); - For homogeneous prefix, we can make an vector where each byte is the least significant byte of the original vector:

let x = load(x); // Duplicate the least significant 64-bit to all 64-bit lanes. // The main motivation is to copy the least significant byte to 64-th position. let b = _mm256_permute4x64_epi64(x, 0); // Within 128-bit (16-byte) lane, set all byte to be the least significant one. let b = _mm256_shuffle_epi8(b, _mm256_setzero_si256()); let mask = _mm256_cmpeq_epi8(x, b);

Now that we have the mask, it is a classical technique to use movemask to collect the mask:

let packed_mask = _mm256_movemask_epi8(mask) as u32;

The $i$-th bit of packed_mask is 1 if and only if the $i$-th byte of mask is 0xFF. So our answer is the number of consecutive 1's in packed_mask. Conveniently, there is a intrinsic to count the number of consecutive 0's in a number:

// Need to invert the bits first

let answer = _tzcnt_u32(!packed_mask) as u8;

And we arrive at a SIMD solution, which requires AVX, AVX2, SSE2, and BMI1 extension on a x86/x86_64 processor.

A Failed SIMD Approach

At this point I had another idea: nice MD5s should not be common. Maybe I could use SIMD to quickly rule out MD5s that are not very nice, and only run the SIMD algorithm on potentially nice one.

If we take look at 2 bytes, which are 4 nibbles, we have:

- The probability that they are all digits is $(10/16)^4\approx 15.3\%$.

- The probability that they are all letters is $(6/16)^4\approx 1.98\%$.

- The probability that they are all the same is $(1/16)^3\approx 0.024\%$.

- The probability that they match $\pi$/$e$ is $(1/16)^4\approx 0.0015\%$.

So, my idea was: apart from the initial screening, no additional runtime would be incurred with high probability.

Consider 4 nibbles occupying 4 bytes, we can fit 8 instances in an __m256i and process them simultaneously.

To load the first 4 nibbles of each of [[u8; 16]; 8], we can simply generate an array containing the first 2 bytes of each array, and use the load method above.

// x is `[[u8; 16]; 8]`

let first_2_bytes = x.map(|v| [v[0], v[1]]);

let first_2_bytes = load(unsafe { transmute(first_2_bytes) });

We are filtering hashes that are not very nice, so I deem that the first 4 nibbles of a hash have to be all nice before we further investigate it. We can apply a similar strategy as above, but with 32-bit lanes.

let byte_mask = _mm256_cmpgt_epi8(_mm256_set1_epi8(0x0Au8 as i8), first_2_bytes);

// If any of the bits in a 32-bit lane is not 1, set all 32 bits to 0

let mask = _mm256_cmpeq_epi8(first_2_bytes, _mm256_set1_epi8(0xFFu8 as i8));

// movemask for each 32-bit lane, 8 lanes total

let packed_mask = _mm256_movemask_ps(_mm256_cvtepi32_ps(mask)) as u8;

There are only $2^8=256$ different packed_mask, so we build a look up table such that each packed_mask is mapped to a u32 where indices of 1's in packed_mask are packed together. For example, if packed_mask=0b0110_1110, where bit-index 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 are 1's, we map to a u32 of 0x00076432. Observe that we use 1-indexing in u32, so that we can easily detect whether there are more by a zero-test.

Given the packed indices, we can initialize the answers to 0, and only compute hashes that has potential.

// `indices` stores the packed indices

let answers = [0; 8];

while indices != 0 {

let idx = (indices & 0xF) as usize - 1;

// Use SIMD algorithm to compute the actual number

answers[idx] = count_leading_digits_simd(x[idx]);

indices >>= 4;

}

The algorithm will report 0 if the number is less than 4, as opposed to the accurate number from the algorithms above.

When computing multiple metrics, to avoid loading an array multiple times, a small optimization would be to OR all the masks together and only generate __m256i for the corresponding arrays.

// We have multiple masks from different metrics

let mask = mask_1 | mask_2 | mask_3;

// SAFETY: MaybeUninit is always initialized

let mut simds: [MaybeUninit<__m256i>; 8] = unsafe { MaybeUninit::uninit().assume_init() };

while indices != 0 {

let idx = (indices & 0xF) as usize - 1;

simds[idx].write(load(x[idx]));

indices >>= 4;

}

It turns out that, although the performance of this approach is better than baseline, it is still much slower than the previous SIMD algorithm. So, I call this a failed attempt.

Performance Comparison

Benchmark System

| Component | Detail |

|---|---|

| CPU | Intel Core i7-6700K |

| RAM | 32GB DDR4 2400MHz |

| OS | 5.15.0.56-ubuntu-22.04.1-lts |

| Rust | 1.66.0 |

| RUSTFLAGS | -C target-cpu=native |

Best Case Throughput

Computing all the metrics

Method Block Size1 Throughput Baseline 16 43.980 Melem/s SIMD 2 280.26 Melem/s Failed SIMD 8 147.88 Melem/s Computing number of consecutive digits as prefix

Method Block Size1 Throughput Baseline 1 85.079 Melem/s SIMD 4 860.68 Melem/s Failed SIMD 8 181.60 Melem/s Computing number nibbles equal to $\pi$ as prefix

Method Block Size1 Throughput Baseline 1 368.23 Melem/s SIMD 4 780.78 Melem/s Failed SIMD 8 517.12 Melem/s ... other metrics results omitted ...

The number of inputs to process in a single invocation. For baseline and SIMD, it is simply a for-loop.

Random String Generation

It might be statistically the same to iterate the input space sequentially, but it is definitely less fun. So, I went with generating random inputs. Obviously we don't need a cryptographic secure random string generation. My requirements are simple:

- String has length 32 and each character is from

[0-9a-z]. - Each valid string has a non-zero probability to appear.

Mainly the input space is so large that I don't really care about the quality of the randomness. We will use SmallRng from rand crate for the source of randomness.

Baseline

I simply compute a random byte modulo 36, and map that to [0-9a-z] to generate a random character:

// `POOL` is a map from `0-35` to `[0-9a-z]`

const POOL: [u8; 36] = [ /* omitted */ ];

let v: [u8; 32] = unsafe {

transmute([

rng.next_u64(),

rng.next_u64(),

rng.next_u64(),

rng.next_u64(),

])

};

let my_random_string = v.map(|b| POOL[(b % 36) as usize]);

SIMD

[u8; 32] fits perfectly into a __m256i, so it is natural to try SIMD. Given a random byte, I really want to use _mm256_rem_epu8 to have the same behavior as the baseline algorithm. Unfortunately, that is part of SVML and not a part of Rust intrinsics. Hence I resorts to the following:

- Take 6 bits from a random byte (0-63).

- Subtract 36 if the byte is greater than or equal to 36.

- Adjust the byte to

[0-9a-z].

This way we make sure that every character has non-zero probability to appear. And the randomness is not too skewed.

// Load 128 random bits

let v = _mm256_loadu_si256(

[

rng.next_u64(),

rng.next_u64(),

rng.next_u64(),

rng.next_u64(),

]

.as_ptr()

.cast(),

);

// Keep 6 bits (0-63)

let v = _mm256_and_si256(v, _mm256_set1_epi8(0x3Fu8 as i8));

// Mask bytes in range 36-63

let gt_35 = _mm256_cmpgt_epi8(v, _mm256_set1_epi8(35));

// Subtract 36 for those bytes

let v = _mm256_sub_epi8(v, _mm256_and_si256(_mm256_set1_epi8(36), gt_35));

// Set each byte to 0xFF if it should be a letter (10-35), otherwise 0x00

let alpha_mask = _mm256_cmpgt_epi8(v, _mm256_set1_epi8(0x09u8 as i8));

// Shift each byte so that range starts at ASCII `0`

let to_numbers = _mm256_add_epi8(v, _mm256_set1_epi8(0x30u8 as i8));

// Shift bytes that should be a letter by additional 0x27, so that the range

// starts at ASCII `a`

let to_alphas = _mm256_and_si256(_mm256_set1_epi8(0x27u8 as i8), alpha_mask);

// Add shifting together to get correct bytes

let v = _mm256_add_epi8(to_numbers, to_alphas);

let mut my_random_string = [0; 32];

_mm256_storeu_si256(my_random_string.as_mut_ptr().cast(), v);

Performance Comparison

| Method | Block Size | Throughput |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 16 | 25.383 Melem/s |

| SIMD | 32 | 107.15 Melem/s |

Looking through benchmark results for each method, the performance generally improves as the block size increases.

MD5 Hash

After I implemented computing all the metrics and generating random strings, I ran some preliminary benchmarks, which showed that computing MD5 hashes was indeed the bottleneck. When I first started the project, I didn't really want to implement MD5 myself. But at that point, it seems inevitable for me to at least investigate.

Baseline

We establish baseline using md-5 provided by RustCrypto.

use md5::{Digest, Md5};

pub fn digest_md5(buf: [u8; 32]) -> [u8; 16] {

Md5::digest(buf.as_slice()).into())

}

Inline Assembly

md-5 does have a feature asm that uses an assembly implementation from Project Nayuki. However according to this issue, the implementation does not work on x86_64-pc-windows-msvc target due to mismatching calling conventions. Unfortunately, that is the target of my developing machine, so I think it is a good time I start to investigate the inline assembly of Rust.

Basics of Rust Inline Assembly

For what we concerned, Rust's inline assembly is a macro call with 2 parts: instructions and register specifications (I omit various configuration options here). Instructions is basically a string template, with each instruction separated by \n. A little quality of life feature by asm!() is that programmer can also write multiple strings separated by comma, and the macro will automatically concatenate them by \n. The second part is a list of registers the assembly requires. Programmers are able to specify specific registers to use, or have the compiler automatically allocate registers with constraints. Programmers also need to specify whether each register is an input, an output, or some other combinations, and the compiler will generate glue code between assembly code and Rust code.

A quick example from Rust By Example:

asm!(

"mov {0}, {1}",

"add {0}, 5",

out(reg) o,

in(reg) i,

);

We can see this works very much like format!() with a little bit more custom syntax.

Basics of MD5

The MD5 algorithm takes data in chunks of 512 bit, with the last chunk padded. For each chunk, the data is regarded as 16 32-bit integers in little endian. And the algorithm maintains 4 32-bit integers as state. The algorithm has 4 rounds, using 4 operators known as f, g, h, and i. In each round, every input integer gets to mix with the state integers in different orders.

For example, f operator looks like follows:

fn operator_f(a: u32, b: u32, c: u32, d: u32, t: u32, s: u32, k: u32) -> u32 {

(((c ^ d) & b) ^ d).wrapping_add(a)

.wrapping_add(k)

.wrapping_add(t)

.rotate_left(s)

.wrapping_add(b)

}

And a sneak peek of the first round looks like follows:

// `a`, `b`, `c`, `d` are 4 state integers, and `data` is the input

a = operator_f(a, b, c, d, data[0], 7, 0xd76aa478);

b = operator_f(d, a, b, c, data[1], 12, 0xe8c7b756);

c = operator_f(c, d, b, a, data[2], 17, 0x242070db);

d = operator_f(b, c, d, a, data[3], 22, 0xc1bdceee);

/* ... Omitted 12 more invocations in the first round ... */

For a complete explanation of MD5, read The MD5 algorithm (with examples).

Implement MD5 for x86-64

We can do one small optimization for our case. We know our input is always 32 bytes, so the padding of the data is fixed:

| Position | Content |

|---|---|

data[0..8] | Input data |

data[8] | 0x80 |

data[14] | 0x100 |

data[9..14] and data[15] | All 0 |

So, for data known to be 0, we can shave 1 add instruction from the operator.

On x86-64, we have lots of registers available, so we can load all 4 state integers, all 8 input integers into registers, with 2 more registers used for temporaries.

We need to perform the same operators on different registers inputs many times, so we need something like a function, but not involving the calling overhead. In other words, we want a macro.

In asm!(), apart from using positional substitution, we can also name the registers like in format!(). And our inline assembly would look like:

asm!(

/* inline assemblies */

// state integers

a = inout(reg) state[0],

b = inout(reg) state[1],

c = inout(reg) state[2],

d = inout(reg) state[3],

// input integers

x0 = in(reg) data[0],

x1 = in(reg) data[1],

/* x2-x15 omitted */

// clobbered temporaries

tmp0 = out(reg) _,

tmp1 = out(reg) _,

);

So the macro needs to take ident of the register, and generates appropriate string. One thing we need to be careful is that since we operates on 32-bit integers, all registers have to appear like {reg_name:e} in the template string. Let's see a first attempt to write operator_f.

#[cfg_attr(rustfmt, rustfmt_skip)]

macro_rules! op_f {

($a: ident, $b: ident, $c: ident, $d: ident, $t: ident, $s: literal, $k: literal) => {

concat!(

"mov {tmp0:e}, {", stringify!($c), ":e}\n",

"add {", stringify!($a), ":e}, {", stringify!($t), ":e}\n",

"xor {tmp0:e}, {", stringify!($d), ":e}\n",

"and {tmp0:e}, {", stringify!($b), ":e}\n",

"xor {tmp0:e}, {", stringify!($d), ":e}\n",

"lea {", stringify!($a), ":e}, [{tmp0:e} + {", stringify!($a) ,":e} + ", $k ,"]\n",

"rol {", stringify!($a), ":e}, ", $s, "\n",

"add {", stringify!($a), ":e}, {", stringify!($b), ":e}\n",

)

};

}

This already looks awful and close to unreadable. It is also really error-prone to write this. Note I put #[cfg_attr(rustfmt, rustfmt_skip)] at the top?, this is how it looks if I don't do that:Truly incomprehensible after formatting

macro_rules! op_f {

($a: ident, $b: ident, $c: ident, $d: ident, $t: ident, $s: literal, $k: literal) => {

concat!(

"mov {tmp0:e}, {",

stringify!($c),

":e}\n",

"add {",

stringify!($a),

":e}, {",

stringify!($t),

":e}\n",

"xor {tmp0:e}, {",

stringify!($d),

":e}\n",

"and {tmp0:e}, {",

stringify!($b),

":e}\n",

"xor {tmp0:e}, {",

stringify!($d),

":e}\n",

"lea {",

stringify!($a),

":e}, [{tmp0:e} + {",

stringify!($a),

":e} + ",

$k,

"]\n",

"rol {",

stringify!($a),

":e}, ",

$s,

"\n",

"add {",

stringify!($a),

":e}, {",

stringify!($b),

":e}\n",

)

};

}

So we need an instruction level abstraction to make it much easier to read:

// stringify an operand

#[cfg_attr(rustfmt, rustfmt_skip)]

macro_rules! asm_operand {

(eax) => { "eax" };

(ebx) => { "ebx" };

/* ... omitted transcribing all the register names ... */

($x: ident) => {

concat!("{", stringify!($x), ":e}")

};

($x: literal) => {

stringify!($x)

};

([ $first: tt $(+ $rest: tt)* ]) => {

concat!("[", asm_operand!($first) $(, "+", asm_operand!($rest))* ,"]")

};

}

// stringify a block of instructions

#[cfg_attr(rustfmt, rustfmt_skip)]

macro_rules! asm_block {

// Instructions separated by semicolon

// Each instruction is an operator followed by one or more operands

// NOTE: does not handle 0 argument operator, labels, etc.

($($op: ident $a0: tt $(, $args: tt)*);+ $(;)?) => {

concat!(

$(

stringify!($op), " ",

asm_operand!($a0) $(, ", ", asm_operand!($args))*,

"\n"

),+

)

};

}

Now we can rewrite our op_f to:

#[cfg_attr(rustfmt, rustfmt_skip)]

macro_rules! op_f {

($a: ident, $b: ident, $c: ident, $d: ident, $t: tt, $s: literal, $k: literal) => {

asm_block!(

mov tmp0, $c;

add $a, $t;

xor tmp0, $d;

and tmp0, $b;

xor tmp0, $d;

lea $a, [$a + tmp0 + $k];

rol $a, $s;

add $a, $b;

)

};

}

This looks much more readable, and closer to actual assembly. Note that we change $t: ident to $t: tt, for later use in x86 version. As a matter of fact, we have a tiny "type system" here to enforce the input type of the macro:

identmeans a register,literalmeans an immediate,ttmeans anything: a register, an immediate, or a memory address[reg1 + reg2 + imm].

We can easily invoke op_f by:

asm!(

op_f!(a, b, c, d, x0, 7, 0xd76aa478),

op_f!(d, a, b, c, x1, 12, 0xe8c7b756),

op_f!(c, d, b, a, x2, 17, 0x242070db),

op_f!(b, c, d, a, x3, 22, 0xc1bdceee),

/* ... omitted the rest of MD5 algorithm ... */

// state integers

a = inout(reg) state[0],

b = inout(reg) state[1],

c = inout(reg) state[2],

d = inout(reg) state[3],

// input integers

x0 = in(reg) data[0],

x1 = in(reg) data[1],

/* x2-x7 omitted */

// clobbered temporaries

tmp0 = out(reg) _,

tmp1 = out(reg) _,

);

And it becomes straightforward to implement MD5 and apply our little optimizations.

Implement MD5 for x86

In an ideal world, I could use the exact same assembly as in x86-64 and call it a day. Unfortunately, we need 14 general registers for our asm!() call. However, on x86, we only have 7 general registers. One idea is to keep input on stack and use a register to store the address of it. This reduces the number of registers needed to 7. However, the code is not guaranteed to compile. We need to manually specify each register to use, save and restore those registers to utilize them.

asm!(

// Save esi and ebp

"sub esp, 8",

"mov [esp], esi",

"mov [esp + 4], ebp",

// Move address of data to ebp

"mov ebp, edi",

// op_f needs to be changed to use esi and edi as temp register

op_f!(eax, ebx, ecx, edx, [ebp], 7, 0xd76aa478),

op_f!(edx, eax, ebx, ecx, [ebp + 4], 12, 0xe8c7b756),

op_f!(ecx, edx, ebx, eax, [ebp + 8], 17, 0x242070db),

op_f!(ebx, ecx, edx, eax, [ebp + 12], 22, 0xc1bdceee),

/* ... omitted the rest of MD5 algorithm ... */

// Restore esi and ebp

"mov esi, [esp]",

"mov ebp, [esp + 4]",

"add esp, 8",

// state integers

inout("eax") state[0],

inout("ebx") state[1],

inout("ecx") state[2],

inout("edx") state[3],

// input integers

in("edi") data.as_ptr(),

// clobbered temporaries

lateout("edi") _,

);

SIMD

There is no way to apply SIMD to generate one MD5 hash. But we can fit 8 32-bit integers into a __m256i, so it is natural to compute 8 MD5 hashes simultaneously using SIMD.

The biggest roadblock is the lack of rol in SIMD intrinsics. But no big deal, rol is just 2 bit shiftings followed by an or. One might try this:

unsafe fn rotate_left(x: __m256i, by: i32) -> __m256i {

let hi = _mm256_slli_epi32(x, by);

let lo = _mm256_srli_epi32(x, 32 - by);

_mm256_or_si256(hi, lo)

}

Well this does not work, if we look closer at the signature of _mm256_slli_epi32 we shall see

pub unsafe fn _mm256_slli_epi32(a: __m256i, const IMM8: i32) -> __m256i;

^^^^^

IMM8 must be a constant, although the documentation is using the legacy const generics syntax, which makes it really hard to spot. One might go ahead and write:

unsafe fn rotate_left<const BY: i32>(x: __m256i) -> __m256i {

let hi = _mm256_slli_epi32(x, BY);

let lo = _mm256_srli_epi32(x, 32 - BY);

_mm256_or_si256(hi, lo)

}

Not really working, because we only have min_const_generics, which means 32 - BY is not considered a constant that can be used for the purpose of const generics. I had to settle with this:

unsafe fn rotate_left<const L: i32, const R: i32>(x: __m256i) -> __m256i {

debug_assert_eq!(L + R, 32);

let hi = _mm256_slli_epi32(x, L);

let lo = _mm256_srli_epi32(x, R);

_mm256_or_si256(hi, lo)

}

Not the best solution, but it works. Implementation for the MD5 rounds is easy:

unsafe fn op_f<const L: i32, const R: i32>(

mut a: __m256i,

b: __m256i,

c: __m256i,

d: __m256i,

t: __m256i,

k: u32,

) -> __m256i {

let k = _mm256_set1_epi32(k as i32);

let mut tmp = _mm256_xor_si256(c, d);

a = _mm256_add_epi32(a, t);

tmp = _mm256_and_si256(tmp, b);

tmp = _mm256_xor_si256(tmp, d);

a = _mm256_add_epi32(a, k);

a = _mm256_add_epi32(a, tmp);

a = rotate_left::<L, R>(a);

_mm256_add_epi32(a, b)

}

And the invocations look like:

a = op_f::<7, 25>(a, b, c, d, x0, 0xd76aa478);

d = op_f::<12, 20>(d, a, b, c, x1, 0xe8c7b756);

c = op_f::<17, 15>(c, d, a, b, x2, 0x242070db);

b = op_f::<22, 10>(b, c, d, a, x3, 0xc1bdceee);

Performance Comparison

| Method | Block Size | Throughput |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 32 | 8.5480 Melem/s |

| Assembly | 8 | 10.229 Melem/s |

| SIMD | 8 | 59.416 Melem/s |

The assembly version does not have much of a performance gain over baseline, which is in line with the observation by Project Nayuki. The SIMD version gives us quite some performance boost.

Putting It Together

I quickly put everything together:

- $n$ (default to be the value of

available_parallelism()) threads to generate random strings, compute their MD5s, and compute metrics. Each thread maintains the thread-local best for each metric and passes that to the main thread every 1024 (a hand-wavy constant I chose) strings generated. - One thread to update the terminal UI.

- Main thread maintains the global best and notifies the UI thread for updates.

For the terminal UI, I wanted a live update UI like vnstat -l or wget. Unfortunately, tui only supports full-screen app. My workaround was to use indicatif, and customize the appearance of the progress bars to make it look like a live update.

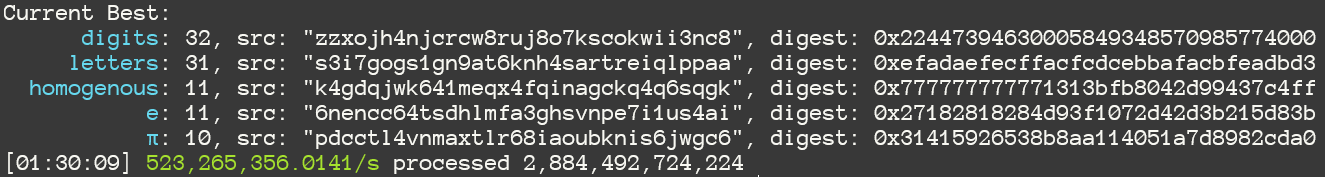

On my developing machine (AMD Ryzen 5900X), when running 24 workers, I can get about 0.5B strings generated and tested per second.

Thoughts

Overall, this is quite a nice little pet project to get me familiar with SIMD and inline assembly in Rust, arguably one of the unsafest part of Rust. The result performance is within my expectation. I do have some thoughts on what can be improved to smooth out the developing experience:

Supporting SIMD on both

x86andx86-64is a pain. Every import turns into two, and rust-analyzer won't automatically add a new import into the other one. It could easily become#[cfg(target_arch = "x86")] use std::arch::x86::{ __m256i, _mm256_add_epi32, _mm256_and_si256, _mm256_loadu_si256, _mm256_or_si256, _mm256_set1_epi32, _mm256_set1_epi8, _mm256_slli_epi32, _mm256_srli_epi32, _mm256_storeu_si256, _mm256_xor_si256, }; #[cfg(target_arch = "x86_64")] use std::arch::x86_64::{ __m256i, _mm256_add_epi32, _mm256_and_si256, _mm256_loadu_si256, _mm256_or_si256, _mm256_set1_epi32, _mm256_set1_epi8, _mm256_slli_epi32, _mm256_srli_epi32, _mm256_storeu_si256, _mm256_xor_si256, };Not a fan. I had to make this macro

macro_rules! use_intrinsic { ($($item: tt), + $(,)?) => { #[cfg(target_arch = "x86")] use std::arch::x86::{$($item), +}; #[cfg(target_arch = "x86_64")] use std::arch::x86_64::{$($item), +}; }; }and I can write

use_intrinsic! { __m256i, _mm256_add_epi32, _mm256_and_si256, _mm256_loadu_si256, _mm256_or_si256, _mm256_set1_epi32, _mm256_set1_epi8, _mm256_slli_epi32, _mm256_srli_epi32, _mm256_storeu_si256, _mm256_xor_si256, }Though I now completely lose the ability to automatically add imports through rust-analyzer. One may suggest

#[cfg(target_arch = "x86")] use std::arch::x86::*; #[cfg(target_arch = "x86_64")] use std::arch::x86_64::*;But this makes my editor very laggy.

No perfect solution either way, and I wonder whether some improvements can be made here.

Trying to keep DRY when using inline assembly is hard. I do think with more careful design, my little

asm_operand,asm_blockmacros may be able to grow into a more robust library to provide better user experience when writing inline assembly. I do hope more experienced community member can chime in and explore the idea with me.I do think it is a bug that a piece of code only compiles with

#[inline(never)], so I hope this issue gets addressed. Most importantly#[inline(never)]is only a hint, so it shouldn't affect whether the compilation succeeds or not.I like the fine control of the

target_featureattribute. This allows me to compile the code without-C target-cpu=native, but still get SIMD after runtime detection if my CPU supports it. But this forces the function to beunsafe, for good reason. But if I want to have a trait for both non-SIMD implementation and SIMD implementation, I will run into a dilemma:- I can make two traits, one for safe Rust (non-SIMD), and one for unsafe Rust (SIMD). But DRY be damned.

- I can make a safe function, assuming runtime checks has been done, calls the unsafe SIMD function. But I technically create a safe function that is unsound, lose the protection from compiler, and rely on downstream developers to read the documentation.

- I can still make a safe function, but adding

assert!()to asserts the existence of the features required. But if I am so desperate that I use SIMD, that will be an expensive one in a hot loop.

At the end of the day, I made some compromises. I added

debug_assert!()for feature detections in my function to hope bugs could be caught while running tests, benchmarks and so on.I thought of a system which uses type system to guard detection of feature. Here is a sketch

trait Feature { fn detect() -> bool; } // Bunch of feature types struct SSE2; impl Feature for SSE2 { fn detect() -> bool { is_x86_feature_detected!("sse2") } } struct AVX2; impl Feature for AVX2 { fn detect() -> bool { is_x86_feature_detected!("avx2") } } impl<F0> Feature for (F0) where F0: Feature, { fn detect() -> bool { F0::detect() } } impl<F0, F1> Feature for (F0, F1) where F0: Feature, F1: Feature, { fn detect() -> bool { F0::detect() && F1::detect() } } /* omitted more impl for longer tuple */ /* omitted some macro magic to make a larger tuple into-able to its subset */ #[derive(Clone, Copy)] struct FeatureToken<T>(PhantomData<T>); impl<T: Feature> FeatureToken<T> { fn new() -> Option<Self> { if T::detect() { Some(Self(PhantomData)) } else { None } } } // we can have functions like this fn this_fn_needs_sse2_and_avx2(a: u32, b: u32, _: FeatureToken<(SSE2, AVX2)>);The only way

FeatureToken<(SSE2, AVX2)>can be created is by testing features, so the type system should ensure that such function is only called when we actually does the runtime feature detection, and tested feature exists.I think the legacy const generics syntax in documentation is easy to miss

pub unsafe fn _mm256_slli_epi32(a: __m256i, const IMM8: i32) -> __m256i; ^^^^^We almost never encounter this syntax anywhere else in Rust, and it is easy to skim over it. I think

rustdocshould make this easier to spot.

One more thing: the friend who sent me the link did a crude CUDA implementation in C++ (to solve a simplified version) after seeing me having fun with this. His preliminary result showed about 40B/s on a 3070. I might revisit this one day to try out Rust-CUDA, but that's the story for another day!